HTML Preview One Page Fact Sheet page number 1.

Learn more @ www.gfm.tl or contact:

Maritime Boundary Ofce

Council for the Final Delimitation of Maritime Boundaries

Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste

e: [email protected] tel: +670 7742 5544

FACT

SHEET

2016

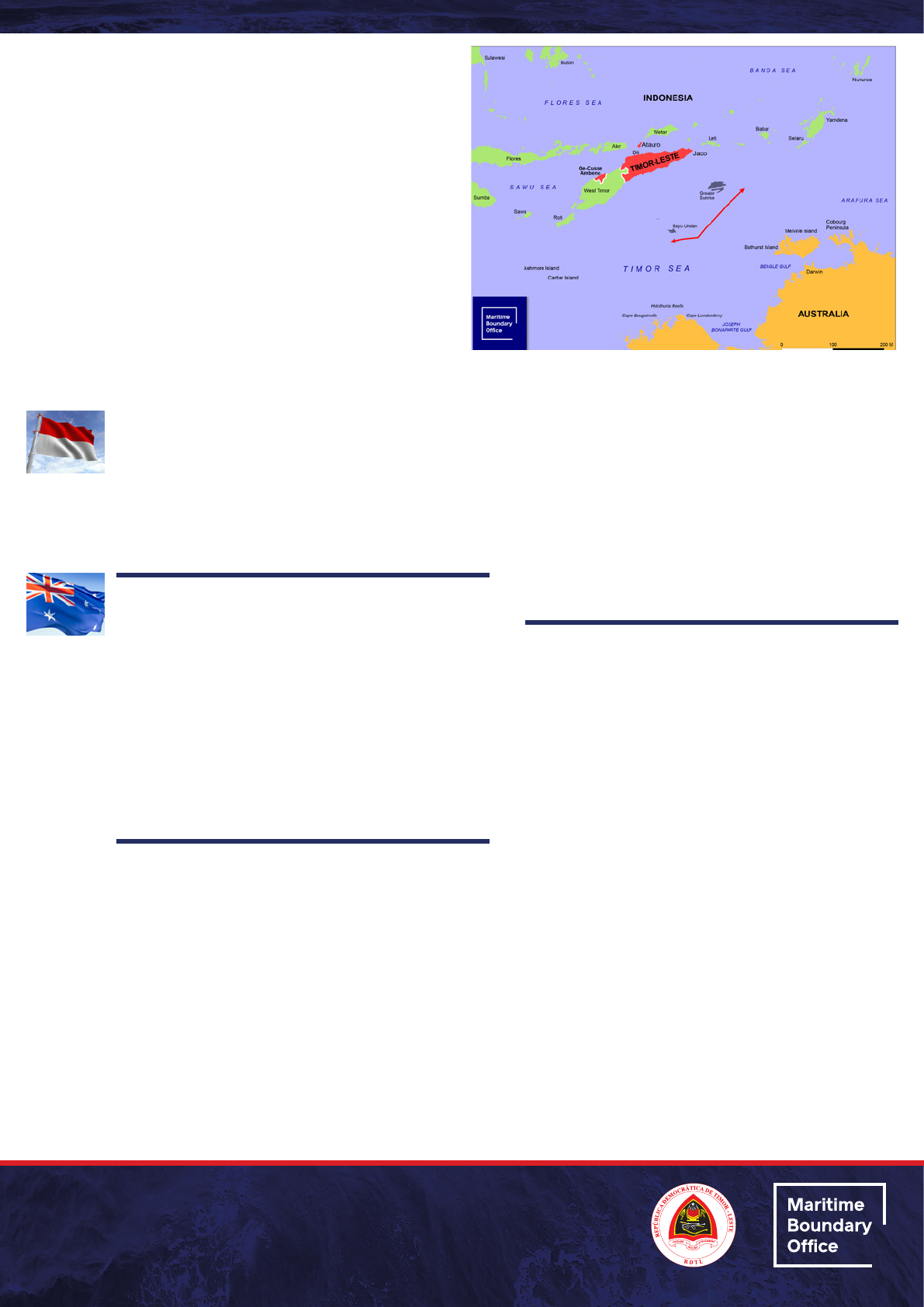

TIMOR-LESTE AND ITS

MARITIME BOUNDARIES

Timor-Leste seeks to delimit permanent

maritime boundaries according to

international law, including the 1982

United Nations Convention on the Law of

the Sea (UNCLOS).

At present, Timor-Leste does not have any permanent

maritime boundaries with either of its two neighbours:

Indonesia and Australia.

Maritime boundaries are a matter of sovereignty for the

people of Timor-Leste.

PROGRESS WITH INDONESIA

• In 2015, Timor-Leste commenced discussions with

Indonesia on maritime boundaries. Indonesia and

Timor-Leste have committed to negotiating a permanent

maritime boundary according to international law.

• Timor-Leste respects the condentiality of this ongoing

negotiation process.

WITHDRAWALS AND REFUSALS FROM AUSTRALIA

• Timor-Leste has no direct means to delimit a maritime

boundary with Australia because:

– In March 2002, two months before Timor-Leste’s

restoration of independence, Australia withdrew

from the compulsory dispute settlement procedures

related to maritime boundaries under UNCLOS, which

excludes the possibility of any court or tribunal

decision on maritime boundaries, and

– Australia also refuses to negotiate permanent maritime

boundaries on a bilateral basis.

THE TEMPORARY ARRANGEMENTS WITH AUSTRALIA

• Australia and Timor-Leste have entered into three

provisional revenue-sharing treaties regarding oil and

gas resources in the Timor Sea. These treaties do not

set permanent maritime boundaries and expressly

state they are without prejudice to either countries’

rights concerning the nal delimitation of their maritime

boundaries.

• The treaties give Australia far more rights than what it is

entitled to under international law.

• The 2002 Timor Sea Treaty was signed on the very rst

day of Timor-Leste’s restoration of independence, 20

May 2002, and largely continued the 1989 Timor Gap

Treaty which Australia negotiated with Indonesia during

the occupation.

• Timor-Leste is currently disputing the validity of

the 2006 CMATS Treaty at the Permanent Court of

Arbitration at The Hague after obtaining evidence of

alleged Australian espionage during the negotiations

which led to the 2006 treaty.

INTERNATIONAL LAW IS THE ‘EQUIDISTANCE / RELEVANT

CIRCUMSTANCES APPROACH’

• UNCLOS requires a maritime boundary delimitation to

achieve “an equitable solution” and further, that States

shall not “jeopardise or hamper the reaching of the nal

[maritime boundary] agreement.”

• For States with overlapping claims (like Timor-Leste

with its two neighbours), international courts and

tribunals, notably the International Court of Justice,

have rened and now entrenched the ‘equidistance /

relevant circumstances approach’ to maritime boundary

delimitation under UNCLOS and customary international

law (see, for example, The Black Sea Case (2009)).

• The approach typically starts by drawing a provisional

equidistance line between two countries. The second

step is to adjust that line to take account of ‘relevant

circumstances’, such as the presence of islands, the

effect of concave or convex coasts and the disparity

in coast lengths. The nal step is to apply a non-

disproportionality test.

• Drawing the provisional equidistance line is therefore

just the rst step in a three-step process.

• Under international law, the ‘equidistance / relevant

circumstances approach’ would apply to all of Timor-

Leste’s maritime boundaries.

Map of what a maritime boundary would look like using equidistance / relevant

circumstances approach under international law.